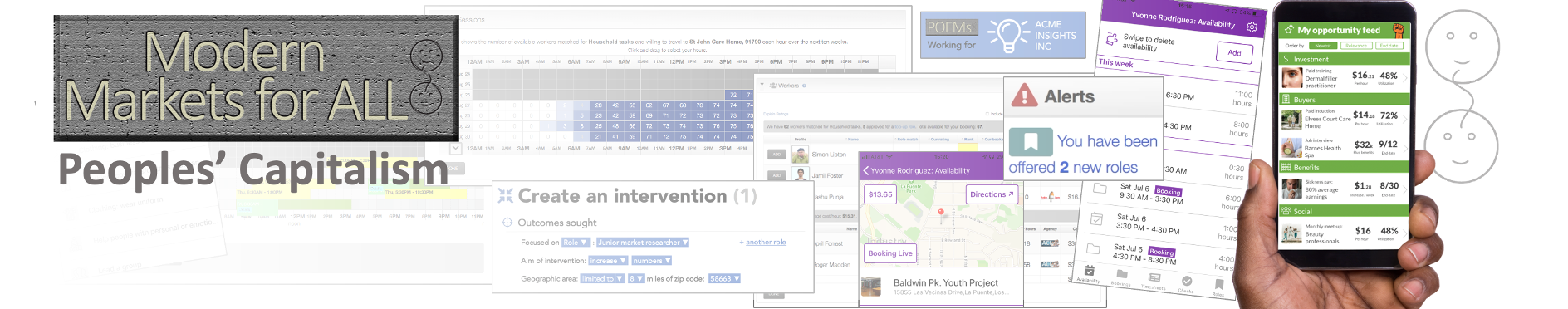

Modern Markets for All thinking dates from 1994; before Google, Facebook, even eBay. Making it real involved missteps, setbacks, and compromises, but a lot of actionable learning.

Modern Markets for All thinking dates from 1994; before Google, Facebook, even eBay. Making it real involved missteps, setbacks, and compromises, but a lot of actionable learning.

Contrarian, but happening

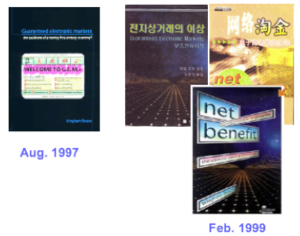

The notion that governments initiate a system of online markets as a regulated public utility originally seemed obvious. Policymakers always ensure significant new technologies deliver maximized economic growth if the private sector can’t. But a 1997 book by UK journalist Wingham Rowan outlining the possibilities, and his second book in 1999, published internationally, were out of synch with the times.

The notion that governments initiate a system of online markets as a regulated public utility originally seemed obvious. Policymakers always ensure significant new technologies deliver maximized economic growth if the private sector can’t. But a 1997 book by UK journalist Wingham Rowan outlining the possibilities, and his second book in 1999, published internationally, were out of synch with the times.

Rowan’s titles were quickly sidelined in stores by books like Dow 36,000 then Dow 40,000 and finally Dow 100,000. Their authors were off in breathless projections about the Dow Jones Index. It didn’t breach 30,000 until 2017. But their core assumption – that corporates would be left to drive the emerging internet, raking in huge profits – was spot-on.

There is an Overton Window of policy ideas considered acceptable at any time. Modern Markets for All was outside it. So, our attention turned to one aspect of the vision; problems of low-skilled individuals needing work that fits around day-today fluctuations in their medical issues, family caregiving, studying, existing partial employment, or parenting. Public agencies support job seekers in all sorts of ways, including national networks of labor exchanges and online platforms offering an alternative to commercial job boards. Why not extend services to irregulars with empowering new markets for hourly labor?

Working with public agencies, politicians, employers, unions, and educators, we developed the technology required. Our learning was open sourced, with fledgling market operations on two continents.

This learning unfolded over four phases:

PHASE 1: Expounding (1994-2000)

Unlike historic campaigns to turn new technology into public infrastructure, Modern Markets for All has its roots in a TV show about online sex. Wingham Rowan was producer/anchor of “cyber.cafe” which, airing from 1995, explored how foot fetishists, exhibitionists, “adult babies”, alien abductees, and others were finding community on the emerging internet.

Being part of that early explosion of online activity led to off-duty thinking about the internet’s potential to bring individuals in from the economic fringes. And how governments could easily accelerate that. Articles, books and policy papers followed.

London think tank Demos organized experts to scrutinize Rowan’s idea of “Public Benefit Computer Trading” from 1994. That led to a 1997 book: Guaranteed Electronic Markets: Backbone of a 21st Century Economy?

London think tank Demos organized experts to scrutinize Rowan’s idea of “Public Benefit Computer Trading” from 1994. That led to a 1997 book: Guaranteed Electronic Markets: Backbone of a 21st Century Economy?

With help from Charles Handy, a leading futurist, a 1999 follow-up book was published internationally: Net Benefit: Guaranteed Electronic Markets, the Ultimate Potential of Online Trade. The two titles foresaw a “sharing economy” and its limitations.

Prime Minister Tony Blair’s report defining UK digital policy featured a section about this thinking on page 94.Press coverage was generally kind, occasionally baffled. Our concept of governments using their leverage to catalyze new markets made it onto BBC news, Radio 4’s Today show, The Sunday Times, Daily Telegraph, The Independent and a two-page spread by Handy in The Guardian. In the US there was an hour long phone in on National Public Radio, coverage in technology magazines and multiple “think pieces”.

PHASE 2: Failed builds (2000-2002)

A dot.com incubator, followed by consulting giant PricewaterhouseCoopers, saw commercial potential in the markets described in Rowan’s books. They provided funding while Adecco, the world’s biggest staffing agency and Informix, now part of IBM, joined with his start-up to make the markets a reality.

But the complex technologies required under-the-hood couldn’t be made to work at the scale required at that time. After two failed software builds, the company was disbanded. Interest in the non-commercial route continued from think tanks on the right and left. But it was infinitesimal compared to attention paid to the dot.com boom then bust.

PHASE 3: 20 City launches (2005-2013)

Rowan spent 2002-2005 working with a volunteer technologist to re-scope the technologies required for these markets. Visualized in interlinked PowerPoints, the new iteration was then tested on a spectrum of potential users.

That exercise culminated in a £500,000 ($680,000) award from Britain’s Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, to try another build. The focus was using new markets to ensure people needing work to fit around ever-changing medical issues, care-giving, parenting needs, or studying had the best possible work opportunities. That tech. finally worked.

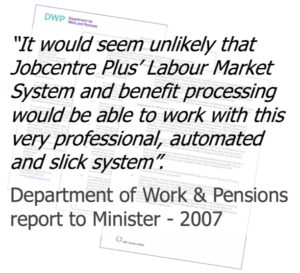

The UK government’s Department of Health, and Cabinet Office provided further funding. But Department of Work & Pensions (DWP), the UK labor ministry, opposed the initiative. They argued government should focus solely on job creation, not bits of employment. Internal papers, obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, also revealed officials worried their floundering IT systems couldn’t interface with the new irregular work platform.

The UK government’s Department of Health, and Cabinet Office provided further funding. But Department of Work & Pensions (DWP), the UK labor ministry, opposed the initiative. They argued government should focus solely on job creation, not bits of employment. Internal papers, obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, also revealed officials worried their floundering IT systems couldn’t interface with the new irregular work platform.

Despite DWP making clear they wanted the initiative stopped, 20 city governments enabled a market. It was unexpected. Britain has unusually centralized government even by European standards. But, opposed by DWP, these were timorous launches on a small scale. We progressively learned you can’t launch such sophisticated markets incrementally. There needs to be a critical mass of demand on day one. (This counter-intuitive point is explained in our recent manual for US public agencies.)

a market. It was unexpected. Britain has unusually centralized government even by European standards. But, opposed by DWP, these were timorous launches on a small scale. We progressively learned you can’t launch such sophisticated markets incrementally. There needs to be a critical mass of demand on day one. (This counter-intuitive point is explained in our recent manual for US public agencies.)

Tesco, a supermarket and Britain’s biggest private sector employer, decided to join the program but eventually opted for a closed system; available to their staff alone. That created further scattered implementations.

By end 2010, regime change at DWP allowed a case to be made for approved launches. New ministers went on front pages to announce these markets were to become a key part of the “Universal Credit”; a bold plan to replace Britain’s byzantine welfare system with one credit. As planning for a merged platform began, the faltering individual city markets were wound down. At the same time Zero-hour contracts were becoming an increasing issue for UK workers.

By end 2010, regime change at DWP allowed a case to be made for approved launches. New ministers went on front pages to announce these markets were to become a key part of the “Universal Credit”; a bold plan to replace Britain’s byzantine welfare system with one credit. As planning for a merged platform began, the faltering individual city markets were wound down. At the same time Zero-hour contracts were becoming an increasing issue for UK workers.

But, even by the standards of government IT schemes, the Universal Credit was a spectacular failure. The overarching program is now five times over budget and many years behind schedule. Non-core services like ours were jettisoned as public employment agencies around the UK became paralyzed. In parallel, Rowan’s operation made some mistakes and began to wind down. But it was clear no other country had created markets like this. A copy of the technology was put in a new non-profit for open sourcing. Key personnel transferred.

PHASE 4: Stateside (2016-present)

Advice from British consulates led to the US. Their well-funded Public Workforce System is ideally placed to catalyse the stakeholders required for launch of markets we call CEDAH’s (Central Database of Available Hours). Nothing comparable was on their horizon. A philanthropist provided seed funding for exploration.

US Dept. of Labor, Aspen Institute, Living Cities, National Governor’s Association, National Association of State Workforce Agencies, National Association of Workforce Boards and Governing magazine promoted these markets to US workforce boards.

By July 2017, 25 workforce bodies (national, state and large-city) had collaborated on a report funded by Annie Casey Foundation. It explored the significant potential, and challenges, of launches in the US. A key issue; federal funding for workforce boards should only be used to support traditional job-creation, not non-standard employment.

By July 2017, 25 workforce bodies (national, state and large-city) had collaborated on a report funded by Annie Casey Foundation. It explored the significant potential, and challenges, of launches in the US. A key issue; federal funding for workforce boards should only be used to support traditional job-creation, not non-standard employment.

In early 2018, the 7 workforce boards of Los Angeles County signed off an open letter to philanthropies saying they wanted to take the lead in preparing for US launches. Kauffman Foundation and Wells Fargo Foundation resourced a market testing team.

The project won US Conference of Mayors’ prize for best job or economic development initiative in America. That drove national interest. Plans for a first launch with the City of Long Beach, focused initially on the events, hospitality and elder care sectors, had to be abandoned as Covid started. A pivot to responsive at-home childcare was announced. Federal funding to provide as-needed childcare for low-income essential workers started in November 2020.

As we were progressing to launch, “gig work” become an inflammatory issue across California with the passing of Assembly Bill AB5 which aimed to tackle misclassification, one of the problems, faced by some of the people, trapped in irregular work. Gig work companies spent $205m to overturn the bill with Proposition 22 just 11 months after it became law. In December 2019, 35% of Americans were reliant on at least some gig work. That could easily be 50% in 2021. The idea that aggressive Silicon Valley companies will shape so much of a post-Covid labor market is now disturbing for many people.