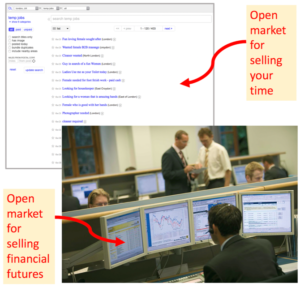

A Wall Street trader sells $100m: market platforms empower him, while charging 0.5% or less.

A Wall Street trader sells $100m: market platforms empower him, while charging 0.5% or less.

A single mom seeks work: platforms control, destabilize, and cheapen her, retaining 30%.

It’s the new normal.

Marking a market

Economic activity is increasingly fluid. That makes markets pivotal. For example, someone in a job will access the labor market every few years, using job-boards to start discussions with employers. But as people have to rely on gig work, they can be in and out of the market every few hours in search of a next assignment. Platforms they use decide what they do, where they go, who they work for, and what they’re paid.

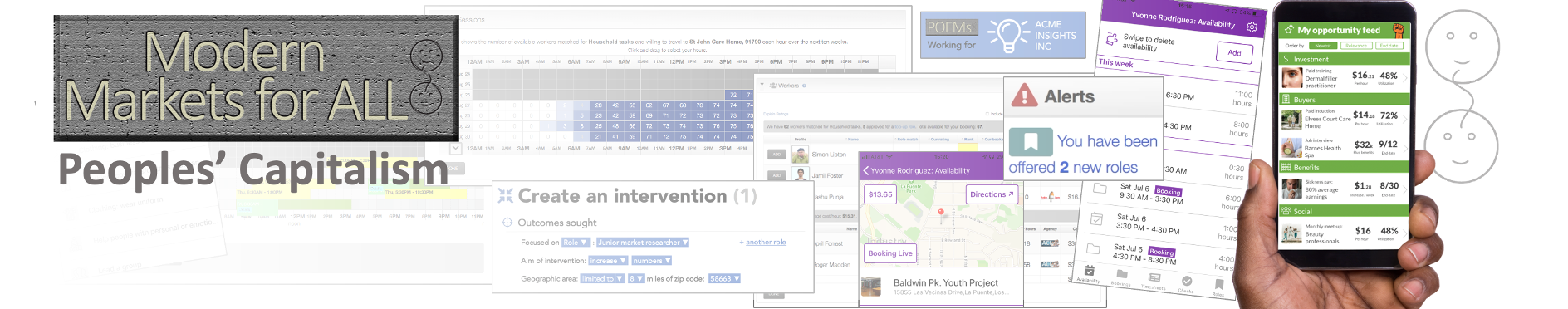

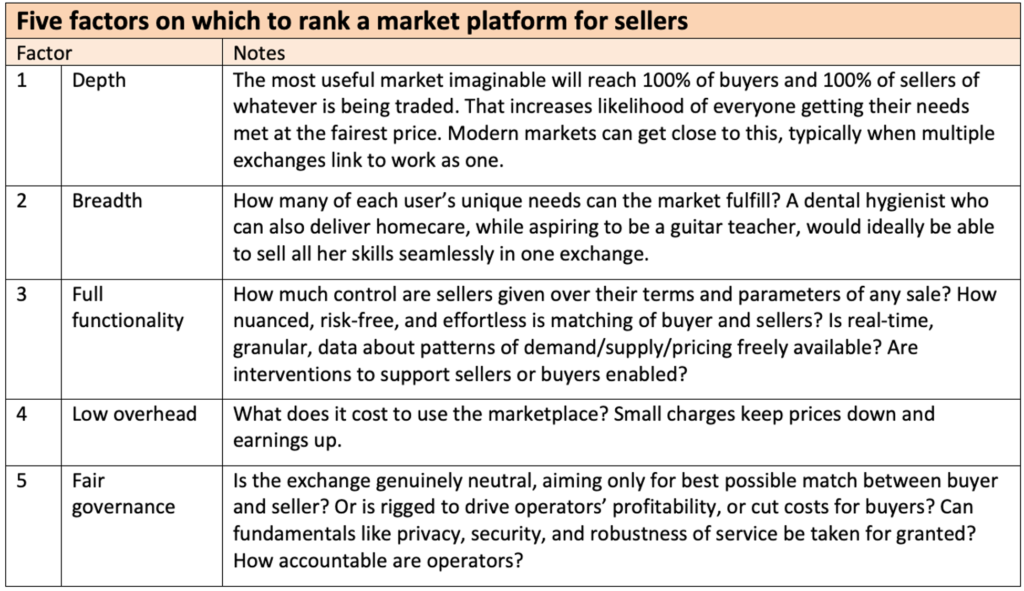

Beyond employment; services, travel, finance, and other parts of the economy are splintering in ways that drive up usage of marketplaces. But how good are these exchanges? Any forum in which sellers find buyers can be ranked on 5 fundamental factors.

Advances in authentication, connectivity, processing, fulfillment, network security, interoperability, data mining, and payments have dramatically increased the ability to deliver markets with all 5 factors. But these Modern Markets technologies are distributed unevenly.

To see the difference that’s making, let’s compare two ambitious twentysomethings, a quarter of a mile apart. It’s Monday morning, both are in search of economic opportunity.

Trader Joe

Joe works on the global desk at a hedge fund in the world’s foreign exchange epicenter; London, UK. He believes the US dollar will fall against the Euro today and wants to sell $100m to be bought back later.

Joe works on the global desk at a hedge fund in the world’s foreign exchange epicenter; London, UK. He believes the US dollar will fall against the Euro today and wants to sell $100m to be bought back later.

USD/EUR is a vast market with buyers meeting sellers on public and private exchanges plus “dark pools”. He uses trading software that accesses all exchanges, and many pools. It also proactively searches for emerging trading forums.

Sudden release of a big block of currency might lower prices. So Joe’s system breaks the $100m into random tranches to be automatically placed confusingly around the trading forums.

Sudden release of a big block of currency might lower prices. So Joe’s system breaks the $100m into random tranches to be automatically placed confusingly around the trading forums.

In case he’s wrong about the dollar’s fall he imposes “stop orders”. If the likely profit is below a threshold, his sales will halt. There’s also a “collar” that hedges smaller losses. It takes him under a minute to set this up. The trades will be secure; a worldwide settlements system guards against counterparty default.

Sharon in the shadows

Sharon is part of the huge market for hourly labor in Tower Hamlets, London’s poorest borough. A single mother, she’s employed on-demand as a food-server in the Canary Wharf financial district.

Sharon is part of the huge market for hourly labor in Tower Hamlets, London’s poorest borough. A single mother, she’s employed on-demand as a food-server in the Canary Wharf financial district.

That makes her part of a growing, global, world of lower-skilled employment; foraging for work from multiple sources, including the informal economy. This world skews towards women and workers of color.

Today Sharon has arranged childcare but was then not called in to serve food. Work from some other source must be found. But she has to keep herself available tomorrow in case the scheduling system used by her primary employer needs her.

She could ring round temp agencies in search of work today. But she’s low margin; they’re not going to put effort into finding the hours she needs.

Thousands of online services claim they can connect Sharon to on-tap employment. Like so many others, she churns through them in search of opportunity. Ride-hailing through Uber was her entry point. But she then did some research, reading how Uber have been caught slashing pay, misleading work-seekers, distorting the market, withholding data, systematically undermining regulation, and spending heavily to roll back worker rights. She knows that risks of any transaction failing can be borne by the drivers.

Thousands of online services claim they can connect Sharon to on-tap employment. Like so many others, she churns through them in search of opportunity. Ride-hailing through Uber was her entry point. But she then did some research, reading how Uber have been caught slashing pay, misleading work-seekers, distorting the market, withholding data, systematically undermining regulation, and spending heavily to roll back worker rights. She knows that risks of any transaction failing can be borne by the drivers.

So, today, Sharon has decided to join the 96% of Uber drivers who exit within 12 months. She’s seen a lot of delivery riders in the pandemic and believes it’s a sector from which she could benefit. Where should she start? Deliveroo, Citysprint, Doordash, Just Eat, Beelivery, City Pantry, UberEats, Gophr, Airtasker, and other platforms each serve a few of the households or businesses booking deliveries in her area. But she can only risk listing in two, maybe three, of these services at a time; if she is off doing a booking for platform A, algorithms running platform B can stop her future work for not being responsive.

Platform thicket

Platform thicket

Sharon has other talents that could be remunerative; experience in a distribution depot, and as a cleaner. She’s good with pets or children, and cooks regularly. Her school taught the basics of gardening.

Should she be in markets for those skills instead? Who knows? She has no data to inform her search for opportunity.

So, she arbitrarily decides on two delivery markets then seeks one for petcare. But which? Rover has raised hundreds of millions to slug it out for worldwide dog-walking dominance with rival Wag! who haven’t launched in London yet, but might do so anytime. That would likely involve price subsidies and a marketing blitz that moves her potential buyers out of Rover where she would have built a track record. Sharon gains nothing from these warring labor platforms’ global ambitions. She just needs to sell her range of skills locally.

Registration with the random three services, then waiting for their approval, takes much of the morning with no indication of whether it will be worthwhile. AmazonFlex, as one example, has made unpaid candidates answer questions on 19 training videos, wait weeks to see if they’re approved, then sit constantly tapping their screens to find out if there is work.

Sharon is selling blind, hoping she’s picked platforms that will have many buyers. But she must also hope her chosen platforms aren’t too dominant. Achieving network effects allows them to seriously cut sellers’ income and boost profits. This has been reported – as examples – at Shipt, Lyft, Doordash, Instacart, AmazonFlex, and TaskRabbit.

By lunchtime Sharon hasn’t received a booking. She has no way of knowing it, but algorithms assigning the work might be focused on keeping proven deliverers busy, not taking a risk with new entrants. So, she makes some calls; a friend knows a restaurant missing a dish washer tonight. The work will be cash-in-hand, so no platform retaining 20-30% of her earnings. It also means no protections, possible wage theft, and risk of official detection. Plus she will need to find more childcare.

By lunchtime Sharon hasn’t received a booking. She has no way of knowing it, but algorithms assigning the work might be focused on keeping proven deliverers busy, not taking a risk with new entrants. So, she makes some calls; a friend knows a restaurant missing a dish washer tonight. The work will be cash-in-hand, so no platform retaining 20-30% of her earnings. It also means no protections, possible wage theft, and risk of official detection. Plus she will need to find more childcare.

Massively parallel

Much has been written about contrasts in mobility, income, health, and political power between people like Joe and Sharon. Our focus is the quality of marketplaces available for each to pursue their economic aspirations. As Sharon’s prospects of a regular job recede, her reliance on marketplaces increases. Joe’s entire career is predicated on access to markets.

Today, both are selling small units; Joe’s random currency tranches, Sharon’s hours. Exchanges where Joe sells are 5-factor (above), they work together as a whole; huge numbers of buyers competing for what he offers. Rich, actionable, data is shared. The only way in which Sharon’s exchanges interoperate is their joined-up campaigning to overturn worker rights. Facing incompatible platforms, Sharon must chose between them. So she only has exposure to a small sub-set of the buyers who would pay for her skills, and no data on them.

Joe’s seamless network of exchanges gives him stability; if one fails, activity just diverts to others. But Sharon could diligently develop a strong track record in a siloed market that suddenly shutters taking her immediate flow of work, track record, and buyer relationships with it. Joe’s across-exchanges software will – of course – factor overheads into each selling decision. That forces exchanges to compete over the lowest charges. Sharon’s channels to buyers are fighting for investors; they need to constantly drive up what they extract from her earnings.

Joe’s seamless network of exchanges gives him stability; if one fails, activity just diverts to others. But Sharon could diligently develop a strong track record in a siloed market that suddenly shutters taking her immediate flow of work, track record, and buyer relationships with it. Joe’s across-exchanges software will – of course – factor overheads into each selling decision. That forces exchanges to compete over the lowest charges. Sharon’s channels to buyers are fighting for investors; they need to constantly drive up what they extract from her earnings.

If Joe is mistaken about the dollar falling today, his losses are capped. If Sharon picks the wrong skill to sell, or offers the right skill in the wrong forum? A lot of unpaid time wasted in registration then waiting for work. And she still has to put food on the table tonight.

Many organizations – government and philanthropic – would like to give Sharon a hand-up with targeted training or support. But beyond broad, often ineffective, job training programs, there’s little they can do. There’s no data, tools, or monitoring to underpin day-to-day interventions that would improve prospects in her labor market. In Joe’s world, governments, companies, and speculators regularly intervene in the markets with laser-like precision.

The closing of markets

The issue here is not who has the latest technology. Sharon is scheduled, monitored, possibly sanctioned, by sophisticated software. But she is not in a market in the sense of sellers advancing by improving, then setting their own rates and parameters, while free to experiment. She has been commoditized within a series of modernized ordering systems.

Bastardized markets are waiting for Sharon in all directions. Perhaps she could start selling stuff? Research will show how small sellers are penalized and charges racked up in Etsy, eBay, Amazon Marketplace and the other big forums.

Bastardized markets are waiting for Sharon in all directions. Perhaps she could start selling stuff? Research will show how small sellers are penalized and charges racked up in Etsy, eBay, Amazon Marketplace and the other big forums.

Her best prospect for a neutral, lowest cost, market is 1990’s style bulletin boards. Sounds useful? Look at today’s flexible earning listings on the biggest site; Craigslist.

Sharon can strive to innovate, cultivate customers, or fill gaps in the market. But with her channels to buyers rigged, she can’t really succeed. As with Joe, her buyers want the efficiencies of new trading tools. But business models for that convenience and cost-cutting have produced Balkanized platforms in which Sharon has negligible options, insights, or individuality. It is a tragic waste of her potential for the economy.

Joe and Sharon may be at the economic extremes; there was still a core of steady jobs in the middle of most economies pre-Covid. But new trading tools are eating at it from both ends. Platforms for devalued labor cut costs of workers, constantly tempting companies away from taking on the overheads of long-lasting jobs. Meanwhile, Wall Street’s analytics capabilities drive continuous pressure for staffing “efficiencies“.

Joe and Sharon may be at the economic extremes; there was still a core of steady jobs in the middle of most economies pre-Covid. But new trading tools are eating at it from both ends. Platforms for devalued labor cut costs of workers, constantly tempting companies away from taking on the overheads of long-lasting jobs. Meanwhile, Wall Street’s analytics capabilities drive continuous pressure for staffing “efficiencies“.

And charges imposed by gig work markets might help explain why estimates of offline, off-the-books, work even in developed countries tally it at 11% the size of GDP.

Our two young opportunity seekers are fictitious. But their divergent marketplaces are a new norm around the world. There are efforts to reign in Wall Street’s outsized profitability. But they have only marginal impact. Rather like the attempts to roll back excesses of the “markets” regular people increasingly have to use.

Our two young opportunity seekers are fictitious. But their divergent marketplaces are a new norm around the world. There are efforts to reign in Wall Street’s outsized profitability. But they have only marginal impact. Rather like the attempts to roll back excesses of the “markets” regular people increasingly have to use.