Don’t be surprised that banks and start-ups have fully exploited platform technologies. The problem is: governments aren’t enabling the rest of us to do the same.

Don’t be surprised that banks and start-ups have fully exploited platform technologies. The problem is: governments aren’t enabling the rest of us to do the same.

Simplicity and big sellers

Why did international banks get such empowering markets? They immediately had everything needed to exploit computerized trading. Financial markets feature:

- Simplicity of sale: Change of ownership of a financial instrument can be achieved with just transfer of details inside a database. There are no dependencies, like transport of an item from seller to buyer. So new markets can have instant, reliable, fulfillment

- Cohesive Sellers: Parts of Big Finance are highly concentrated. Nine Wall Street banks control 70% of stock market orders. If those 9 decide they will collaborate to force, for example, competing online stock exchanges to become interoperable, it happens.

- Government enablement: Trust in wide-open, high turnover, markets requires dependable data, swift punishment of dishonest activity, and guaranteed completion of transactions. Government doesn’t just provide the SEC to do this, there are official entities such as the National Market System, Fedwire, government-owned clearing houses, the CFTC, the Mifiid standards and NRSRO’s underpinning a new breed of markets.

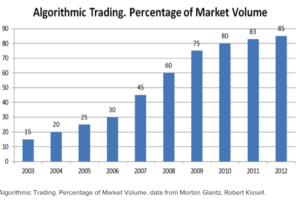

From 1997 new exchanges, led by Island and Archipelago, started exploiting these factors. Reuters and Bloomberg refined the data. In parallel, programmer Thomas Peterffy quietly perfected auto-trading tools. By 1999 his secret was out; Goldman Sachs moved conclusively towards algorithmic trading and the wordwide race to “algo trading” began.

From 1997 new exchanges, led by Island and Archipelago, started exploiting these factors. Reuters and Bloomberg refined the data. In parallel, programmer Thomas Peterffy quietly perfected auto-trading tools. By 1999 his secret was out; Goldman Sachs moved conclusively towards algorithmic trading and the wordwide race to “algo trading” began.

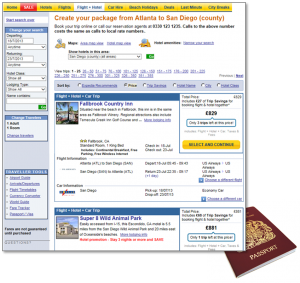

A few other sectors had computer-ready offerings and ability to aggregate sellers into one market. As travel moved online; hotel chains, airlines, and rental car companies coalesced around a “Global Distribution System”. It’s their database of each room, seat, and vehicle; when it is available and how it is to be priced. When we shop on platforms like Expedia and notice a room price fluctuating, it is because of this underlying system. Algorithms working for sellers know exactly what each bed is worth. We don’t.

Meanwhile in the wider world

For most of us, our time is our key economic asset. It’s what employers pay for. Since the 2000’s, low-skill employment has been fragmenting; away from regular jobs to portfolios of hour-by-hour work. That’s driven by fundamentals: a shift from manufacturing to less predictable services, relaxed regulations, corporate short-termism, and diminished unions.

So, there was an opening for new labor platforms. But trading of peoples’ hours does not align with the immediate strengths of computerized commerce. Labor markets feature:

- Nuanced transactions: A financial derivative won’t slink off at lunchtime, insult customers, or nibble your food order. Temporary labor is fraught with these outside-the-database issues; so a computerized market can’t deliver guaranteed quality.

- An atomized seller base: Work-seekers are numerous and diverse; they have no means to aggregate and dictate market requirements. So, platforms are free to profitably focus on what buyers want; get the buyers then sellers have to use whatever market you offer.

- Official passivity: Wall Street requested government underpinning for its solid new markets. Nobody did the same for labor markets. Governments sat back but then had to scramble to firefight abuse of sellers.

Because of these factors, no new large-scale, neutral, labor market emerged. Big employers moved to their own internal “markets” with 2015’s Workforce Central 8 as the breakout enabling platform. Meanwhile, Uber catalysed an opportunity for tech. investors. Using technologies developed in government programs, Uber focused on a tight niche – unregulated taxi journeys – starting in 2009.

Uber could disempower workers to cut costs. Drivers go where they’re told, for what Uber’s algorithm decides they’re worth. (Uber takes disproportionate flak in coverage of gig work. That’s because of scrutiny after they became the most valuable private company ever. We have little idea what thousands of platforms aiming to replicate Uber’s valuations in other sectors are doing.)

Politicians sit it out

Why did governments allow low-quality labor markets to proliferate? Politicians could have enabled, then incentivized, tech. companies to build empowering platforms. Public bodies are typically the biggest buyers of labor (directly or through suppliers), the key regulators, and overseers of registries determining who is licensed to do what. They spend billions on boosting employment.

Even in right-leaning countries like the US, government uses this leverage to initiate equitable economic infrastructure.

Public labor exchanges, now branded America’s Job Centers, started in the 1930’s as an alternative to exploitative for-profit agencies. Facilities like this drive vote-winning growth. Around the world, governments commission online labor markets for all types of jobs. These services create an alternative to Monster, Indeed, CareerBuilder and other for-profit platforms. See for example government-initiated job matching services in the US, Canada, Britain and Australia. Why not do the same for uncertain work? (Disclosure: we work with local US agencies on this possibility.)

Public labor exchanges, now branded America’s Job Centers, started in the 1930’s as an alternative to exploitative for-profit agencies. Facilities like this drive vote-winning growth. Around the world, governments commission online labor markets for all types of jobs. These services create an alternative to Monster, Indeed, CareerBuilder and other for-profit platforms. See for example government-initiated job matching services in the US, Canada, Britain and Australia. Why not do the same for uncertain work? (Disclosure: we work with local US agencies on this possibility.)

A chicken-and-egg seems to explain lack of action from the top. With bad markets, data collection is not granular enough to fully detect flexible economic activity. So government economic development services, like America’s Public Workforce System, still have targets focused only on outdated jobs.

Hiding on plain sites

Hiding on plain sites

There have been many efforts to upgrade gig work, with little impact. Why haven’t voters demanded fundamental action? It’s hard to avoid a humbling conclusion about Modern Markets: few people understand what’s happening. And those that do stay quiet.

Walls of screens on a financier’s desk can seem visually unappealing and incomprehensible. It’s easy to assume those displays are tangential to our lives. Meanwhile, the beguiling Uber interface on a phone might feel more immediate, more empowering. It isn’t.

Uber relies on complex routing, pricing, and display technologies. But as a labor market it’s basic. Try telling the App you want to charge more, or to help you assemble a pool of regular customers, or to add a new service you’ve invented. You can’t. Uber has no business case for shaping a worker-centric labor market. That should be clear from their past investment in driverless vehicles. (In January 2020 Uber allowed some freedoms to drivers in California to avoid giving them employee protections. Those options disappeared after gig work companies defeated legal protections for workers.)

Uber relies on complex routing, pricing, and display technologies. But as a labor market it’s basic. Try telling the App you want to charge more, or to help you assemble a pool of regular customers, or to add a new service you’ve invented. You can’t. Uber has no business case for shaping a worker-centric labor market. That should be clear from their past investment in driverless vehicles. (In January 2020 Uber allowed some freedoms to drivers in California to avoid giving them employee protections. Those options disappeared after gig work companies defeated legal protections for workers.)

Schlock and awe

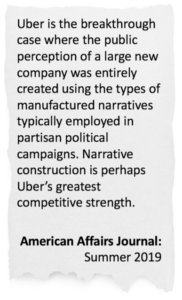

With governments off the pitch, and frantic competition, emerging platforms adopted a Wild West spirit. Uber claimed a superior model accounted for its rapid uptake, but massively subsidized transactions buy customers. Ruthless tax-avoidance was a cornerstone of Amazon’s rise. Food delivery apps have set up unauthorized websites that thwart local delivery alternatives. Room rental site AirBnB got big by hacking Craigslist. But this behavior barely dented politicians’ reverence for services seen as modern utilities.

Denmark’s tourist agency is among several that has partnered with AirBnB despite what’s been called their “Guerrilla War” against local governments. When Austin, Texas, tried to ban global ride-share services, they were overruled by state lawmakers. A “Sharing Economy Review” set up by Britain’s government had the founder of an online home exchange as chair. Amazon is allowed to reshape goverment procurement despite detailed competitor research showing this can drive up costs. Innisfil, Ontario, is just one city that has paid Uber to replace public transit.

Denmark’s tourist agency is among several that has partnered with AirBnB despite what’s been called their “Guerrilla War” against local governments. When Austin, Texas, tried to ban global ride-share services, they were overruled by state lawmakers. A “Sharing Economy Review” set up by Britain’s government had the founder of an online home exchange as chair. Amazon is allowed to reshape goverment procurement despite detailed competitor research showing this can drive up costs. Innisfil, Ontario, is just one city that has paid Uber to replace public transit.

Uber and its imitators are better than older ways for small sellers to find buyers; flyers, classifieds, street hawking. But that doesn’t make them the best markets now possible. Authorities have a long history of ensuring modernized, democratized, economic forums. Confusion, a veneer of showy technologies, and aggressive PR does seem to have quelled that responsibility over the last 20 years.

Uber and its imitators are better than older ways for small sellers to find buyers; flyers, classifieds, street hawking. But that doesn’t make them the best markets now possible. Authorities have a long history of ensuring modernized, democratized, economic forums. Confusion, a veneer of showy technologies, and aggressive PR does seem to have quelled that responsibility over the last 20 years.

→ Consequences of Market Inequality