Income disparities, persistent poverty, diminished public services, hollowed-out jobs, precariousness, corporate power, climate degradation, debt, seething unfairness, systemic risk. Today’s market platforms underpin them all.

Income disparities, persistent poverty, diminished public services, hollowed-out jobs, precariousness, corporate power, climate degradation, debt, seething unfairness, systemic risk. Today’s market platforms underpin them all.

Upwards attraction

Passively allowing a few sectors to develop exponentially superior markets was never going to foster a balanced economy. But how much blame for trends like depressed wages, de-skilling, and economic insecurity that roils politics belongs to this factor alone? We suggest it’s significant.

Passively allowing a few sectors to develop exponentially superior markets was never going to foster a balanced economy. But how much blame for trends like depressed wages, de-skilling, and economic insecurity that roils politics belongs to this factor alone? We suggest it’s significant.

Buyers of any commodity gravitate to the most efficient trading forum. In a domestic example; if a cheaper, faster, more reliable, supermarket opened closer to your home, you would likely shift location for a weekly shop.

New transaction technologies have created three tiers of trading efficiency in any economy:

TIER (1): Modern Markets: Five Factor exchanges, the best possible forums for buyers and sellers.

TIER (2): Modernized ordering systems: Platforms like Uber attract buyers with cheapness and convenience. So sellers have to use them.

TIER (3): The old ways: Plenty of economic activity is still arranged through phone calls, face-to-face interactions, or low-tech websites.

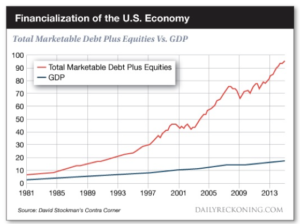

Tier (1) is mostly confined to the global financial system. Their increases in trading efficiency drive financialization, an ongoing suck of resources from less efficient tiers. When datapoints, overheads, responsiveness, and liquidity are so good, cash will perform better in financial maneuverings than the real world. Monetarism and deregulation fed the potency of new markets for Wall Street.

Tier (1) is mostly confined to the global financial system. Their increases in trading efficiency drive financialization, an ongoing suck of resources from less efficient tiers. When datapoints, overheads, responsiveness, and liquidity are so good, cash will perform better in financial maneuverings than the real world. Monetarism and deregulation fed the potency of new markets for Wall Street.

Going into labor

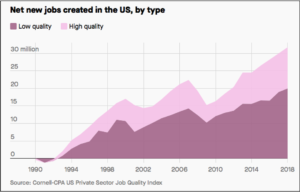

Cornell University’s Job Quality Index quantifies differences between a good job (predictable hours, reasonable pay, benefits, promotion prospects) and a bad one (precarious times, low pay/benefits/prospects). As this second graph shows, bad jobs increasingly dominated as new market technologies impacted the workforce.

Cornell University’s Job Quality Index quantifies differences between a good job (predictable hours, reasonable pay, benefits, promotion prospects) and a bad one (precarious times, low pay/benefits/prospects). As this second graph shows, bad jobs increasingly dominated as new market technologies impacted the workforce.

Market technologies can be bewildering, often unfathomable. But explaining today’s yawning inequalities without referencing them is incomplete. For example, when contextualizing financialization, commentators typically cite deregulation, disintermediation, more precise pricing, increased granularity, and upwards demand for credit.

But, in the same timeframe as financialization, labor markets were also reshaped by deregulation (scaled-back protections), disintermediation (outsourcing to employment agencies), more precise pricing with smaller purchases (rise of on-demand workers) and increased demand (falls in unemployment). How was that for the sellers in these markets? Workers experienced a downturn in relative wealth.

Is globalization the key differentiator between financial and labor markets? Financial assets now ricochet between territories in search of opportunity; labor can’t do that. But workers could have an equivalent. In a perfect labor market, each individual could – if they choose – enjoy informed, frictionless, movement between countless types of work to maximize value of their skills or enthusiasms. We do not have a perfect labor market; lack of data, overheads, and silos keep workers confined.

Is globalization the key differentiator between financial and labor markets? Financial assets now ricochet between territories in search of opportunity; labor can’t do that. But workers could have an equivalent. In a perfect labor market, each individual could – if they choose – enjoy informed, frictionless, movement between countless types of work to maximize value of their skills or enthusiasms. We do not have a perfect labor market; lack of data, overheads, and silos keep workers confined.

Unequal access to markets has reshaped society. That disorienting citizens, it’s hard to see how “the system” is stiffing you.

Below are some other current issues viewed through a market inequality lens:

Harsh externalities

Tier (1) and Tier (2) platforms create a step-change in efficiency within their silos of activity. But they push distortions into the wider economy, many of which drive social problems.

Some examples:

Re-evaluation of assets: Some resources are ideal fodder for Modern Markets. Property for example requires nothing more than amended digital records in a registry for a sale. Leases for buildings can be bundled, securitized, and hold value even if not utilized. Labor, by contrast, is amorphous, unpredictable, and lacks rigid structures. Real estate has climbed in value in the Modern Markets era. Labor has gone the other way.

Re-evaluation of assets: Some resources are ideal fodder for Modern Markets. Property for example requires nothing more than amended digital records in a registry for a sale. Leases for buildings can be bundled, securitized, and hold value even if not utilized. Labor, by contrast, is amorphous, unpredictable, and lacks rigid structures. Real estate has climbed in value in the Modern Markets era. Labor has gone the other way.

- Administrative burdens: Any seller searching for the best possible Tier (2) platform can face registration for multiple services, each with their own business model, geographic strengths, and contractual agreements. If cleaning a house through an app, can you use the bathroom? Some apps allow it, others make it a contractual offense. Sellers have to grasp these subtleties. Widespread use of Dark Patterns adds another front to this battle. The age-old problems of navigating prohibitive bureaucracies for regular people have morphed into faceless, aggressively sold, profit-maximizing, algorithmic processes.

Economic paralysis: Imagine a La Paz resident keen to earn by ferrying bikes up that Bolivian city’s steep hills on the roof of his car. He could set up a business but then be starved if “UberPedal” (ride-hailing with bike racks) arrives in La Paz propelled by Uber’s technology, user base, and subsidies.

Economic paralysis: Imagine a La Paz resident keen to earn by ferrying bikes up that Bolivian city’s steep hills on the roof of his car. He could set up a business but then be starved if “UberPedal” (ride-hailing with bike racks) arrives in La Paz propelled by Uber’s technology, user base, and subsidies.

But that’s assuming UberPedal hasn’t already been cancelled worldwide as authoritatively rumored. As former Soviet citizens will attest; central planning by capricious authorities snuffs economic dynamism.

Sometimes the opportunity killing is blatant. Handy, a platform for tradespeople, has charged cleaners $100 if they and a client form an off-platform relationship (by agreeing to a part-time job for example). Other platforms just contractually ban this kind of progression. Enforcement may not be watertight, but again there’s inhibiting uncertainty.

Bias to bigness: Trading technologies get dramatically more effective with bigger datasets and wider application. That makes expansion a priority for companies that can benefit from those technologies.

Bias to bigness: Trading technologies get dramatically more effective with bigger datasets and wider application. That makes expansion a priority for companies that can benefit from those technologies.

It’s why, for example, one outlet in a chain of fast food restaurants with standard processes and interchangeable staff will now operate with less cost and more flexibility than a family-run café. Lower-profile Tier (2) platforms like Workforce Scheduler give large employers sophisticated tools to manage employment costs precisely. That disadvantages small competitors.

- Systemic risks: Tier (1) markets can reach a point where all sellers have figured out the optimal algorithms for standard trades. So, there has to be ever more complex, but risky, uses of the infrastructure to create a competitive edge. Innovations like derivatives then foster easy credit that imperils everyone, as we learned in 2008.

Would the financial crisis have happened if Modern Markets hadn’t existed, or were evenly spread through the economy? Financiers could still have constructed incomprehensible investment tools, but they wouldn’t have attracted such large proportions of national wealth. Or, those instruments would have been able to speculate equally in assets like human capital. An over-skilled workforce from a bubble in that investment is a nice problem to have.

Would the financial crisis have happened if Modern Markets hadn’t existed, or were evenly spread through the economy? Financiers could still have constructed incomprehensible investment tools, but they wouldn’t have attracted such large proportions of national wealth. Or, those instruments would have been able to speculate equally in assets like human capital. An over-skilled workforce from a bubble in that investment is a nice problem to have.

Gatekeepers get their way

Access to Tier (1) and (2) economic efficiency is controlled by unaccountable gatekeepers. They are often accused of unfair rent-taking. But there are other ways their agenda so often becomes the agenda:

Framing the issues: When a news anchor mentions “The Markets” we know she’s not talking about labor exchanges or other vital forums where buyers and sellers meet. Ensuring markets rise is vital for economic opportunity. But if media and politicians focus primarily on placating financial markets, because they allocate so much resource with such precision, that marginalizes other possible interventions.

Framing the issues: When a news anchor mentions “The Markets” we know she’s not talking about labor exchanges or other vital forums where buyers and sellers meet. Ensuring markets rise is vital for economic opportunity. But if media and politicians focus primarily on placating financial markets, because they allocate so much resource with such precision, that marginalizes other possible interventions.

Organizations at the apex of new trading technologies use their control to set the agenda in countless ways. Voters care about climate change for example. But Wall Street poured increasing sums into fossil fuels because that’s what their markets demand.

- Automation prioritized: Delivery giants say flying drones can solve “the last mile problem”; how to get packages from local hubs onto doorsteps. But that challenge was solved 100 years ago; teens on bikes can deliver goods. And, unlike quadcopters, they will ring doorbells, climb stairs, read notes, even interact with neighbors.

That model gave millions of youngsters earnings, responsibility, purpose in their community, and local networks. But it doesn’t foster corporate advantage. So, investment pours into automation, not building a modernized entry-level labor market.

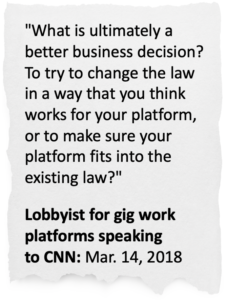

Remaking regulation: Platform companies have become powerful enough to mould laws around their requirements. That spills over to the wider economy. California’s Proposition 22 is a case in point. In January 2020, the state enacted law “AB5” mandating employment rights for gig workers. Doordash, Lyft, Uber and others invested $205m to overturn the law.

Remaking regulation: Platform companies have become powerful enough to mould laws around their requirements. That spills over to the wider economy. California’s Proposition 22 is a case in point. In January 2020, the state enacted law “AB5” mandating employment rights for gig workers. Doordash, Lyft, Uber and others invested $205m to overturn the law.

Prop. 22 achieved that, creating an effective minimum wage calculated at $5.64. Its success juiced gig companies’ valuations by $13bn.

Other states planning their own version of AB5 have likely been deterred.  Meanwhile, throughout America, corporate business plans, financial targets, and operations manuals are starting to demand labor costs that can align with gig platforms.

Meanwhile, throughout America, corporate business plans, financial targets, and operations manuals are starting to demand labor costs that can align with gig platforms.

- Data might: Platform operators can become apex predators. Amazon controls prominence for thousands of sellers, unfairly according to critics. When Amazon launches an own-brand product they can first synthesise data from thousands of third-party sellers on their system, then decide how to compete against them.

Trickles in the torrent

We are floundering in today’s Market Inequality. Tools like redistributive taxes, new benefits, and controls on corporate activity struggle to impact. Minimum wage rises get nullified by the precise ways workforces are now scheduled. Trickling wealth up or down seems powerless against a remorseless updraft of resources into Tier (1) and Tier (2) trading technologies.

Take the most radical solution for inequality; Universal Basic Income. If everyone were to get weekly cash as a right, where would they spend it? Probably big retail platforms, chain eateries, and supermarkets; because those are large enough to run Tier (2) systems that keep costs down. The resulting corporate profits are then in a magnetic pull to Tier (1) activity.

To assess why the traditional inequality toolkit might not be working, it’s worth trying a thought experiment around other vital infrastructure. Imagine a world of Road Inequality: A few institutions have built themselves speedy, asphalted, lit, interlocking, regulated, highways to move their people and goods. Everyone else travels on rutted tracks not ready for motorized vehicles; or uses costly, uncoordinated, toll roads.

That injustice would demand action. Antitrust rules forcing highways to be less harmonized? Tax hikes on asphalt? Subsidies for users of the muddiest paths? Speed limiters on the elite’s vehicles? Perhaps even Universal Free Horses? Each initiative would partially redress the balance. But an enduring solution would start with what most governments did in the early 20th Century: ensure modern, coherent, roads that anyone can use as they wish.

That injustice would demand action. Antitrust rules forcing highways to be less harmonized? Tax hikes on asphalt? Subsidies for users of the muddiest paths? Speed limiters on the elite’s vehicles? Perhaps even Universal Free Horses? Each initiative would partially redress the balance. But an enduring solution would start with what most governments did in the early 20th Century: ensure modern, coherent, roads that anyone can use as they wish.

Market Inequality is less visible. That shouldn’t negate the obviousness of just bluntly leveling the playing field. Initiatives like Universal Basic Income offer immediate fixes to economic pain. But as a system-change strategy, applying them without solving Market Inequality could be like filling a swimming pool without first disabling a pump extracting its water.

→ GAMECHANGER: A Public Utility Option