A legal framework could initiate a new public utility: state-of-the-art online markets built around everything organizations and people at the base of the economy have to sell.

A legal framework could initiate a new public utility: state-of-the-art online markets built around everything organizations and people at the base of the economy have to sell.

Aims of a framework

Aims of a framework

The five key aspirations for a “Modern Markets for All” policy should be:

- Growth: Sustainably increase activity, inclusion, opportunity, incomes, and investment at the base of the economic pyramid while attracting activity out of shadow economies.

- Exploit leverage: Use public agencies’ ability to pump-prime and underpin activity in markets to spread social, environmental, and economic benefits of new marketplace technologies.

- Choices: Add a distinctive public option to sit alongside any number of commercial or charitable marketplaces.

- Avoid costs: Ensure government does not design, fund, or run an officially backed system of markets. All risks are borne by private operators.

- Maximize impact: Infrastructure enabling new markets could also enhance democracy, civic participation, quality of public services, and government accountability.

Structure of the framework

There’s an obvious way to deliver the above aims, widely used by governments of right and left: an official concession. To take one example; determined to finally create a fixed link between Britain and the European continent, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government guaranteed a 33 year monopoly, to a first consortia willing to tunnel or bridge the English Channel. Removing the possibility of competitors attracted billions in investment.

There’s an obvious way to deliver the above aims, widely used by governments of right and left: an official concession. To take one example; determined to finally create a fixed link between Britain and the European continent, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government guaranteed a 33 year monopoly, to a first consortia willing to tunnel or bridge the English Channel. Removing the possibility of competitors attracted billions in investment.

Concessions like this also create self-funding toll-roads, schools, lotteries, airports, bridges, cable TV services, and ferry links. Each concession typically bestows protections or benefits only government can give, for a fixed timeframe, with accompanying obligations on operators. Investors get their return from charges to users.

Applying this model to e-markets could create a robustly independent, for-profit, group of corporations incentivized to drive state-of-the-art trading infrastructure across a country’s micro-economy. The challenge for policymakers is compiling a package of benefits and obligations to initiate the service which we call POEMs (Public Official E-Markets).

What government offer operators

There is a mass of detail behind each of these 5 key offers, see our briefing on enabling legislation for a fuller list.

- Pump priming: Government spending on services and workers, direct or indirect, will go mainly through POEMs.

- Official authentication: POEMs is allowed direct verification – with a user’s permission – of their status or licenses in any government database.

- Automated relationship with courts: POEMs can feed disputes between users into the courts, but only when its own comprehensive mediating technology is unable to nudge parties to a resolution.

- Marketing: Government will promote POEMs through its channels to workers, tourists, businesses, officials, claimants, taxpayers, and inward investors.

- Clarity of status: POEMs’ operators will not be a counterparty in transactions. They can operate financial services.

There is a further facility POEMs could exploit that is easy for policymakers to offer: an official registry of trading records. This stores a unique, objective, record of each user’s successful completion of transactions in POEMs that is given official status; like a driving license. It is under the control of each user but can’t be replaced in case of sanctions, just as we can’t get an alternative driving license having filled the first with penalty points.

This verifiable record of a person or small businesses’ reliability could be used in any way they wish, inside or outside POEMs. It should strongly incentivize good behavior in the markets.

Obligations on operators

The list above creates a sizeable business opportunity. Policymakers mustn’t repeat mistakes made in early days of technologies like mobile telephony and give away the value too cheaply. Five key demands the framework should include:

The list above creates a sizeable business opportunity. Policymakers mustn’t repeat mistakes made in early days of technologies like mobile telephony and give away the value too cheaply. Five key demands the framework should include:

- Universal service: Operators must deliver markets for the full range of legal trades, to any legal buyer, seller, or investor by a given date. Market functionality must be commensurate with the amount of activity in each sector. Automated deduction of tax, administration of welfare, and portable benefits should be an option for any user.

- All funding: Operators pay for everything; the system, interfaces, and modernization for public databases before launch, public POEMs terminals in areas of low internet penetration, peer training for the techno-unconfident, and so on. They must also provide some facilities to users without charge, for example volunteering or voting.

- Market neutrality: Operators can’t buy, sell, invest through, or take a position in any of the markets they operate. They can’t set prices or transaction parameters, only enable users to do so. Anonymized market data must be published. All users are treated equally. Anyone can build additional services, and add charges, on top of POEMs.

- Charging controls: Operators must set a flat-rate percentage mark-up they impose on each transaction. They have no other source of income; no advertising, premium listings, exploitation of user data, extra costs at checkout, premium options, or fees for access. Their cut is subject to a Maximum Average Transaction Size.

- Reallocation in case of failure: if POEMs’ operators breach their obligations, there is an escalating process of public warnings that culminates in transfer of the concession to another provider. Operators’ investment in modernization and training is not repaid. To allow preparation for this, operators must open source, or at least publish, their code.

The business case

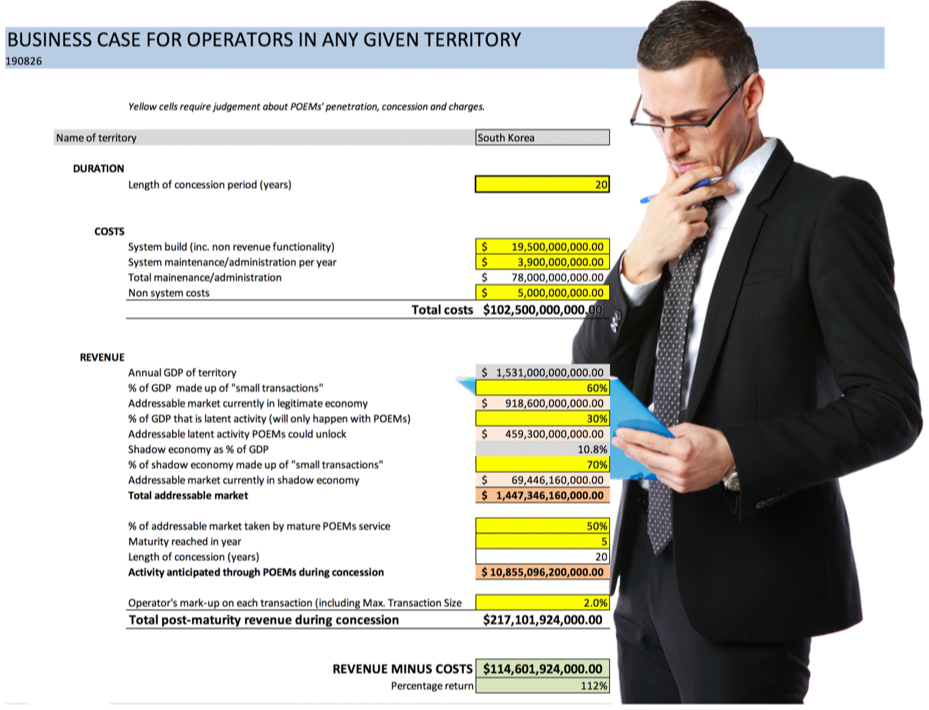

Banks and Big. Tech. sit on cash piles. Would a framework like this induce them to spend it on enabling new economic infrastructure for the less well off? And what would they need to charge users? As a quick test, this spreadsheet assesses the opportunity for a 20 year concession with South Korea as a sample country:

Our first input is costs of building POEMs. Looking around the world for non-optimistic scenarios in complex, official, IT initiatives we alighted on the UK government’s disastrous Universal Credit scheme with its final cost of £15.8bn.

We added annual maintenance at an above-industry-average 20% of original build cost a year, then assumed $5bn for training, ensuring public access, and other non-system costs. That’s a further $102bn required over the 20 years.

Concession winners’ returns are modeled on three factors; (a) existing percentage of GDP made up of the small transactions POEMs will offer, (b) latent activity that becomes viable only because of POEMs and; (c) current shadow activity made up of small transactions. That’s the addressable market. We have assumed POEMs will only ever penetrate 50% of this and it will take 5 years to get there.

These rough calculations suggest even a disastrously launched South Korea POEMs, charging 2% on each transaction, would generate a 110% return for its backers. Actual costs and charges in any jurisdiction could be flushed out in competitive bidding for a concession.

International companies are the best candidates to build POEMs. They have the funds required and would have much to lose if suspected of kowtowing to government at the expense of their users. But they may be bad arbiters of local activity.  So, a POEMs framework could mandate franchising of front-end marketplaces; one local running POEMs’ market for medical procedures, another invested in enabling anyone to do neighbors’ laundry, a third developing the commercial fencing sector, and so on.

So, a POEMs framework could mandate franchising of front-end marketplaces; one local running POEMs’ market for medical procedures, another invested in enabling anyone to do neighbors’ laundry, a third developing the commercial fencing sector, and so on.